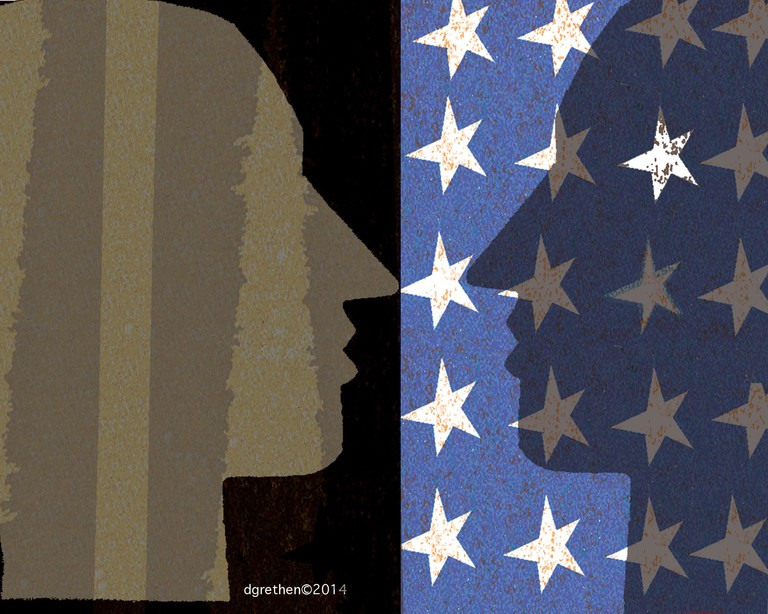

Race and Technology

Servants or slaves? How Africans first came to America matters

This month, we celebrate the quadricentennial of the arrival of the first Africans to America. Many chose to mark this occasion as the beginning of slavery in America. Earlier this year, when embattled Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam appeared on CBS This Morning, he said, "We are now at the 400-year anniversary—just 90 miles from here in 1619. The first indentured servants from Africa landed on our shores in Old Point Comfort, what we call now Fort Monroe, and while…"

Gayle King, the co-host, would have none of it. "Also known as slavery," she cut him off.

And the media had a field day with yet another tone-deaf remark on race by the governor.

As a long-time student of African American history, particularly of that period between 1619 and 1700, I bristled at their exchange. For history is on Northam's side. Gayle King, like so many Americans, black and white, was wrong. The first Africans to arrive in America in 1619 were sold into bondage as indentured servants not as slaves, and that distinction really matters. Many feel that calling these Africans indentured servants somehow white-washes slavery's legacy. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, calling them slaves, obliterates a quintessential aspect of the legacy of slavery and race in America; removes a cornerstone from understanding where we began as nation now divided; and places just beyond our grasp the tools we need to heal.

By 1630, most of these black bondsmen had arguably worked off their indentures and were free. By 1640, slavery, and the racism that undergirded it, had taken hold so firmly in the colonies that even free blacks lived in great peril.

How, then, in two short decades does the status of black colonists — those in bondage and those not — change so dramatically? And, why? In the answers to these questions lie fundamental truths about race and racism in America. Famed historian, the late Lerone Bennett, observed, "[b]efore the invention of the Negro or the white man or the words and concepts to describe them, the Colonial population consisted largely of a great mass of white and black bondsmen, who occupied roughly the same economic category and were treated with equal contempt by the lords of the plantations and legislatures."

Slavery was not an inevitability. Slavery, and the racism behind it, was a choice made by the Byrds, and Mathers, and Winthrops; by the Jeffersons, and Washingtons and the other founding fathers. A conscious choice to exploit the labor of Africans for the economic benefit of the planter-merchant aristocracy.

Well after slavery was established, but still well before the Revolutionary War, Virginia's Lt. Gov. William Gooch sought to rationalize the disenfranchisement of free blacks this way, "[the] Assembly thought it necessary," he explained to the British government, "to fix a perpetual Brand upon Free Negroes and Mulattos by excluding them from the great Privilege of a Freeman… a distinction ought to be made between their offspring and the Descendants of an Englishman, with whom they never were to be Accounted Equal."

Natives, working-class whites, and Africans co-existed in early colonial America. They suffered servitude together, they intermarried, they even rebelled together. But for Africans, always the most vulnerable, their indentured servitude became perpetual servitude, then ultimately outright slavery. Slavery brutalized their bodies, their minds and their spirits, but it did not leave working-class whites unscathed.

Just as the first Africans did not arrive to these shores as slaves, the first working-class whites did not arrive as racists. Racism, brewing among European elites, was taught to the white working class here in the colonies. The same laws that enslaved blacks, circumscribed working-class whites, enforcing what they could and could not do, whom they could and could not love, whom they were and were not better than. From legislatures to churches to newspapers, a racial divide was constructed, and vigorously enforced, in the decades following 1619.

Healing America's racial divide is daunting. The threads of this division are deeply woven into the nation's fabric. Restorative, rather than retributive, justice offers one path forward. A path that begins with an honest discussion about slavery. Slavery was a choice, not an inevitability, for America, and that's why how Africans first came to this country matters.

Reprinted from my op-ed in the Seattle Times. August 29, 2019

Image (c) Copyright Seattle Times by Donna Grethen.